Event Insights: Complex Problem Solving with Ben Shenoy

By IMI | 29th May 2025

You’re certain to have heard the acronyms by now: VUCA, TUNA, and the likes. But Ben Shenoy prefers a word that captures the essence of problem solving in a more realistic way: messy.

Messy problems don’t fit into neat categories. They are characterised by multiple stakeholders, high uncertainty, and emotional as well as cognitive overload. And most of all, they defy quick fixes.

Our most pressing issues have things in common

From climate change to generative AI, from shifting trade tariffs to the future of transport, the most pressing issues of our time are deeply messy. What do they have in common? Ambiguity, anxiety, and a constant pressure to act, even when we don’t fully understand the terrain.

Success, paradoxically, can be dangerous. Shenoy referred to this as the tyranny of success. Just ask Kodak, Nokia or Boeing—companies that once defined their sectors but struggled to adapt when the world changed around them. Nokia, for example, developed touch screen technology five years before Apple but didn’t pursue it because it threatened their existing product line.

Assumptions can be the biggest danger

The deeper issue? Assumptions. We operate based on what we think we know. Whether that’s about industries, business models, customers, or even core institutions like hospitals. But when the environment shifts, those assumptions can become traps. As Mark Twain put it, “It ain’t what you don’t know that gets you into trouble. It’s what you know for sure that just ain’t so”.

Ben identified a number of recurring patterns that show up in messy situations. For example, different stakeholders interpret the same situation in wildly different ways. We’re constantly pulled in opposite directions, and traditional decision-making tools fall short. And thanks to social media echo chambers, our capacity to process complexity is easily overloaded.

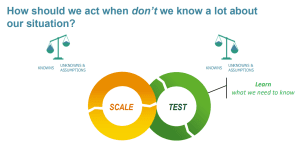

So, how should we act? Our actions should be a function of what you know, what you don’t know, and what you think you know. The specific actions depend on how much you know,

- When you do know what’s going on: Use tried and tested methods. Be decisive. In these cases, agile isn’t always necessary, and waterfall might be more efficient.

- When you don’t know enough: Gather data, seek diverse perspectives, and experiment. But remember, over-analysis can be just as risky as inaction.

- When you think you know but really don’t: This is the danger zone. Check your assumptions. Seek out contradictions. Try to disprove your own viewpoint.

Find the real issue, before you try to solve it

Ben urged us to move from problem-solving to problem-hunting. In other words, we first need to focus on identifying the real issue before rushing to fix it.

For example, the auto industry is navigating a perfect storm of climate regulations, electric and autonomous vehicles, and new competitors. The natural instinct might be to innovate within the old frame of car ownership. But what if the real problem isn’t how to make better cars? What if it’s more about the mobility industry as a whole?

Only 4% of cars are actually in use at any one time. In that context, the business model of owning a car becomes the real assumption to question, and potentially, the biggest opportunity for innovation.

In messy environments, clarity rarely arrives all at once. Instead, it emerges through curiosity, reflection, and constant challenge. Ben’s parting advice? Be wary of certainty. Stay open. Hunt for the real problem.

Because in the end, it’s not the unknowns that catch us out: it’s the things we’re sure about, that just aren’t true.