Olive Fives: Experiment to achieve more as a hybrid team

By Olive Fives | 25th January 2022

Trial and error is key to leaders optimising team productivity, writes Olive Fives.

PwC’s 2021 Remote Work survey found both employers and employees agree that although remote working has been successful, time in the office is valuable for collaboration and relationships, and therefore a hybrid approach (40-60% office work) would be optimal.

This presents leaders with certain challenges in satisfying human and productivity needs: establishing how much time a team needs to be together in person to maximise productivity and build and maintain positive relationships; finding the correct balance of synchronous and asynchronous work, and balancing autonomy with supervision and reassurance.

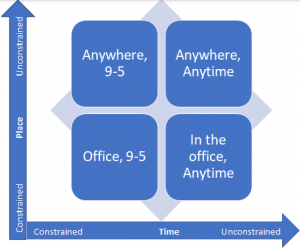

Lynda Gratton of the London Business School frames hybrid working along two axes of time and place: Place, constrained (e.g. in the office) or unconstrained (anywhere), and time, constrained (working with others, synchronously) or unconstrained (working asynchronously).

In the past year, many organisations have adapted from constrained place/time of relatively stable office hours to working from home, maintaining traditional hours. Few moved to a completely unconstrained hybrid model – working anytime, from anywhere – which, given the globalised nature of work today, is interesting: working across continents and time zones makes anywhere/anytime working both practical and productive.

The challenge for leaders is to identify and resolve the trade-offs inherent in hybrid working: suitable roles and tasks; workflow and project impacts; employee preferences (balancing individual and team needs); engagement, fairness, and inclusion.

Not all roles and tasks will smoothly transition to anytime/anywhere, so identifying the drivers of productivity and performance for key roles and tasks is an important first step. What are the energy, focus, coordination, and cooperation demands for each and how will changing working arrangements impact those drivers?

Some roles require long periods of independent, concentrated effort (focus), while others may require synchronous work with others (coordination) or brainstorming and creativity (cooperation). Considering these requirements, which time/place arrangements might work best?

In the past year, many employees have experienced more flexible work arrangements and have likely developed preferences for how, where and when to work. Establishing and balancing their requirements for collaboration and coordination versus independence and autonomy will play a key role in maximising productivity, performance and job satisfaction. There are many ways to stay connected that do not require meetings or synchronous work, for example by exploiting project management software.

Consideration of employee preferences will need to be balanced with the operational workflow and project demands. Rethinking and redesigning workflows is a key element of making hybrid work. Gratton notes the value of employing digital tools for knowledge maps or flowcharts to visualise and analyse how work is done and could be done to inform experiments with new time/place arrangements.

This also allows insight into individual and team workloads, collaboration demands and asynchronous working opportunities, which in turn can inform how technology can support the coordination and productivity of work.

The answers to three key questions are useful in this analysis:

- Are any tasks redundant (e.g. traditional meetings)?

- Can any tasks be automated and/or reassigned (e.g. enabling client signatures online rather than requiring face to face meeting)?

- What new purposes can we imagine for our place of work to encourage collaboration and creativity?

Finally, adjustments in work practices and processes to accommodate a hybrid approach should be considered in the light of fairness, inclusion and organisational culture so, from the outset, engaging the team or a broad and diverse representative group in the design and implementation of the hybrid ‘playbook’ is essential.

To make hybrid arrangements work best, consider how to ensure both place and time principles inform your leadership approach.

From a place perspective, plan the office for cooperation (e.g. large social versus small private spaces, rotating seating arrangements) and ensure working from home is a source of energy with appropriate equipment, regular check-ins, encouraging and respecting available/unavailable signals.

Time principles require balancing synchronous and asynchronous blocks of time. For example, encouraging employees to block out asynchronous focus time to suit both their work rhythms and work demands while ensuring synchronised time maximises coordination and collaboration through debate, feedback and decision making. If synchronous time is virtual, online collaboration tools can be both creative and productive.

To ensure hybrid working boosts job satisfaction, performance and productivity, take the time to experiment and learn what works best, consider and mitigate the inevitable trade-offs of any approach, and spend time really listening to understand and accommodate team member needs.

Ongoing engagement with employees – building, maintaining and reinforcing positive relationships – is a key leadership prerogative in a hybrid environment, spending more rather than less time connecting with remote colleagues.

Olive Fives is an IMI Associate faculty member and an innovative organisational development consultant. She is affiliated with a number of programmes at IMI, including the Professional Diplomas in Strategic HR Management, Management, and Strategy and Innovation, and the MSc in Management Practice.